The Silent Felony: The Legal Architecture That Hunts Male Sex Workers for Sport

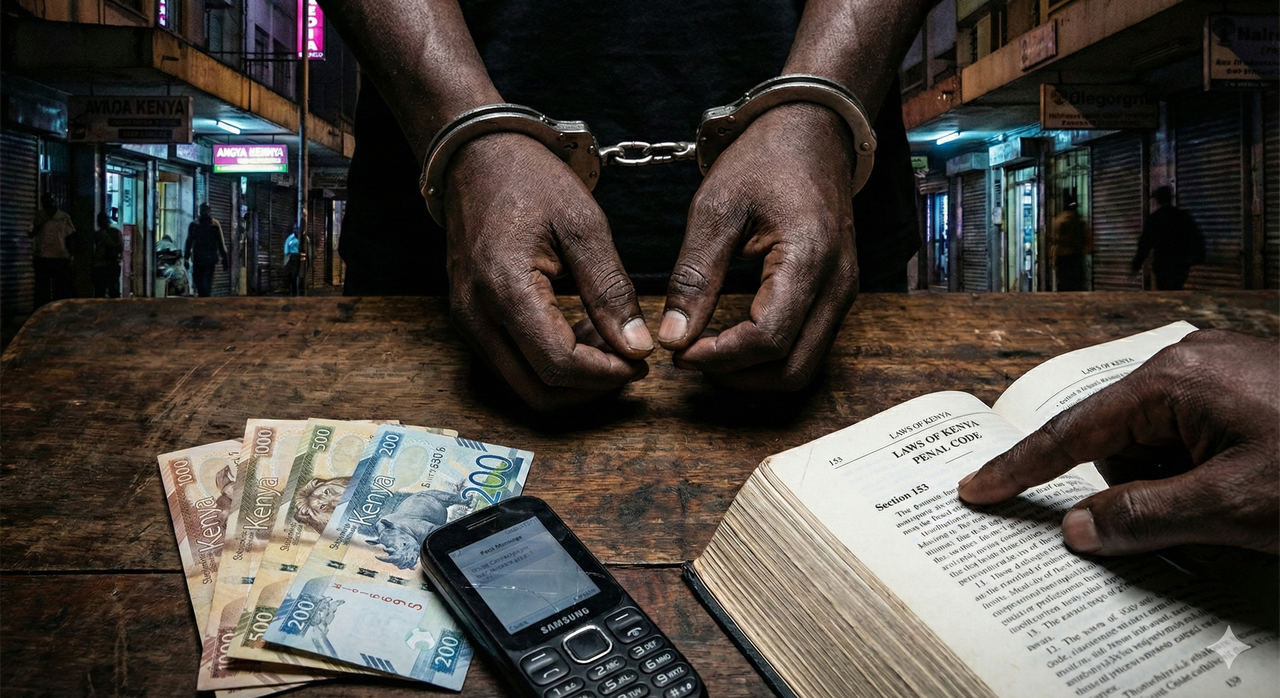

While female sex workers in Nairobi wrestle with county by-laws, askaris, and “loitering” charges, their male counterparts face something much darker: a Penal Code that turns their very survival into a felony.

This feature dissects that legal machinery and shows how it has been weaponised to make male sex workers walking crimes—always guilty, always exploitable.

Part I: The Gendered Trap in the Penal Code

At the heart of this injustice lie two almost identical provisions in Cap 63 – The Penal Code: Section 153 and Section 154.

On paper, both deal with people “living on the earnings of prostitution.” In practice, they function very differently.

The Tale of Two Sections

| Feature | Section 153 – Targets Men | Section 154 – Targets Women |

|---|---|---|

| Wording | “Every male person who…” | “Every woman who…” |

| Core offence | Knowingly lives wholly or partly on the earnings of prostitution | Knowingly lives wholly or partly on the earnings of prostitution |

| Legal weight | Felony – serious crime | Misdemeanor – minor offence |

| Practical effect | Used to criminalise male sex workers for spending their own income | Historically aimed at madams/pimps who exploit others |

| Consequences | Long jail terms or crippling extortion | Small fines, brief detention, or release after plea |

The Built-In Double Standard

Read literally, Section 153(1)(a) doesn’t just target pimps. It targets any male person who “lives on the earnings of prostitution.”

That means:

- If a man pays his rent with sex work income → he’s a felon.

- If he buys food, pays fare, or pays school fees → he’s a felon.

A woman in the same line of work is more likely to be treated as a misdemeanour offender. A man is structurally coded as a serious criminal.

Part II: The Anatomy of the Legal Trap

For male sex workers, every stage of their hustle is criminalised. There is no legal route through the system.

Trap 1: The Promotion – “Soliciting for Immoral Purposes”

Any attempt to market services—standing on a corner, posting on an app, using coded language online—can be framed under provisions tied to soliciting for immoral purposes.

Police and undercover officers know how to use this:

- Fake clients

- Recorded chats

- Sting operations in lodgings

The “crime” is not violence or exploitation. It’s the mere act of signalling availability.

Trap 2: The Act – “Unnatural Offences”

For many male sex workers, especially those serving male clients, the sexual act itself is criminalised under Sections 162 and 165:

- “Unnatural offences”

- “Gross indecency between males”

These carry heavy penalties—reportedly up to 14 years—completely disproportionate to consensual acts between adults.

Trap 3: The Livelihood – “Living on the Earnings”

Even if the act and soliciting are never proven, lifestyle becomes evidence:

- A man suspected of sex work who cannot explain his income.

- M-Pesa statements showing repeated payments from “clients.”

- Being found in known hotspots.

Under Section 153, survival itself becomes the crime.

Police don’t have to prove exploitation. They just have to show:

“You are a male person. You earn from prostitution. You live on that income.”

Felony established.

Part III: Voices from the Shadows

“Kevin”, 26 – Westlands

“They don’t want to take you to court. Court is work. They want your M‑Pesa.”

Kevin explains how a “client” booked him through an app and lured him to a Ngara lodging.

“Three men burst in. They quoted Section 153 like they are judges. ‘You are a male living on earnings of prostitution. That’s 14 years.’ They demanded 50k. I sent 20k. They laughed and walked out.”

For Kevin, the law is not a book; it’s a weapon pointed at his SIM card.

“John”, 32 – CBD

“When kanjo pick up the girls on Koinange, it’s a nuisance. They pay a fine, they are back. For me, if I go to report a client who beat me, I become the criminal.”

He has scars from a beating by a violent client. He never reported.

“If I walk into a station bleeding, they’ll ask where I was, who I was with, what I do. By the time I finish, I’ll be in the cell. The man who attacked me will go home.”

Part IV: A Constitutional Time Bomb

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution looks very different from these Penal Code relics.

What the Constitution Says

- Article 27(4): The State shall not discriminate on any ground, including sex.

- Article 28: Every person has inherent dignity and the right to have that dignity respected and protected.

Yet male sex workers are:

- Punished more harshly than women for the same economic activity.

- Denied meaningful access to justice and protection.

- Exposed to violence and extortion because reporting crime exposes them to prosecution.

The Human Cost

| Impact Area | Reality for Male Sex Workers |

|---|---|

| Police violence | Beatings, forced strip-searches, and threats of “evidence photos” shared with family |

| Extortion | Demands for cash or sex by police and fake clients using Penal Code threats |

| Health access | Fear of arrest at clinics or outreach programs; avoidance of HIV/STI services |

| Mental health | Chronic anxiety, depression, and isolation due to constant criminalisation |

The Verdict: Walking Felonies in a Broken System

For male sex workers in Kenya, the greatest danger is not only the streets, clients, or disease. It is the law itself.

As long as provisions like Section 153 remain, the State has written them into existence as permanent suspects:

- Always guilty if they work.

- Always guilty if they eat from that work.

- Always exploitable by anyone who can quote the law.

This is not justice. It is a silent felony built into the architecture of Kenyan law—a system that hunts a specific class of citizen for sport, while pretending to defend morality.

Disclaimer: This article is for investigative and educational purposes only. The Mwaniki Report does not condone illegal activities. Readers are advised to understand and uphold the laws of Kenya, even as they demand just and constitutional reforms.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)