Ruto’s Gen Z Problem: Why 2027 Will Be Won on the Feed, Not at the Rally

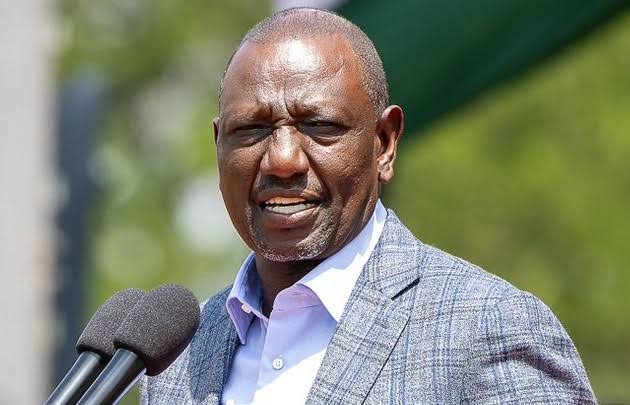

William Ruto’s problem with Gen Z is often framed as a communications glitch or a policing miscalculation, as if a better PR team or a softer riot squad could fix the hostility that exploded during the 2024 Finance Bill protests. Your research points to something deeper. For the first time in Kenya’s electoral history, the battleground is shifting from physical crowds to digital infrastructure. The 2027 contest will be less about who hires the best sound system and more about who controls the architecture of attention itself, and on that terrain Gen Z already operates with a fluency the state has not caught up with.

In this new world, the most powerful tool is not a helicopter landing at a dusty stadium, but an algorithm deciding whose video lands on the For You page. Ruto does not simply face a sceptical youth bloc; he faces an entire youth‑run information ecosystem that he cannot easily buy, coerce, or co‑opt.

From barazas to feeds: who holds the microphone now

For roughly sixty years, Kenyan politics has been scripted around the baraza. A president or senior politician arrives with sirens, a choir sings, MCs hype the crowd, and microphones pass through a carefully controlled lineup. Ordinary citizens are reduced to spectators who clap, heckle, or walk away, but rarely shape the agenda. Power flows from a raised podium down to a captive audience.

Gen Z snapped that script in 2024. When the Finance Bill landed, they did not wait for MPs to organise town halls at county headquarters. They opened TikTok, stitched budget explainers, turned X Spaces into rolling public hearings, and used WhatsApp groups to convert outrage into exact meeting points and march routes. Instead of one microphone in a field, thousands of young Kenyans became broadcasters in their own right, each pushing content into feeds that could reach across estates and counties in minutes.

The centre of political gravity shifted in that moment. The real baraza is no longer a physical field with plastic chairs; it is the endless scroll of the For You page. The loudest speakers at a rally cannot compete with one meme or one emotional live‑stream that the algorithm decides to show to millions. For Ruto 2027, this means that crowd size and convoy length will matter less than whether his story, or his critics’ story, dominates the screens that Gen Z actually look at.

The invisible stack: how Gen Z built a parallel political internet

Most coverage of the 2024 protests focused on the visible action, the placards, crowds, running battles, teargas and bodies on tarmac. What sits underneath that spectacle is an invisible stack of tools, channels and workflows that now function like a parallel political internet maintained by young Kenyans themselves.

Researchers mapping those months describe small teams of coders, designers and community managers quietly running the back‑end. They built Telegram bots that answered legal questions, Telegram or WhatsApp channels that posted live routes and safe exits, protest maps that updated as police lines shifted, and bail and medical funds coordinated through shared sheets and verified till numbers. Some even spun up custom AI assistants that could turn dense Finance Bill clauses into simple Sheng, generate placard slogans on demand, or draft scripts for what to say when stopped by police.

None of that infrastructure is tied to any party headquarters or presidential campaign. It sits in the hands of micro‑collectives, volunteer organisers and independent creators who answer to their peers, not to State House. The tools they used to mobilise against new taxes can be repurposed almost as they are for voter registration blitzes, get‑out‑the‑vote reminders, parallel vote tallies and rapid fact‑checking on election night.

That is why your framing of a “shadow digital IEBC” lands so sharply. There is now a youth‑run operating system for civic action in Kenya, layered across TikTok, X, WhatsApp and custom bots, that no campaign can fully own yet every serious candidate must learn to navigate.

Ruto versus the feed: when the state feels like spam

Once the state realised that Gen Z had captured the high ground of attention online, it fell back on tools it understands best: intimidation, control, and managed narratives. Instead of building genuine dialogue inside those digital spaces, authorities and allied elites tried to colonise them from above. They paid troll farms, flooded hashtags with counter‑messaging, slid into DMs with threats, and at key moments even throttled or cut access to blunt protest momentum.

From the point of view of a security planner, this may have looked like strong crisis management. From the point of view of an algorithm, it looked like low‑quality, low‑trust content. Platforms like TikTok and X reward authenticity, spontaneity and emotional honesty. They punish stiff talking points chopped into clips, polished graphics with hollow slogans, and obviously coordinated hashtag campaigns. Young Kenyans learned to spot this “state content” instantly and reacted with mockery, quote‑tweets, stitches and duets that taught the algorithm to treat official messaging as something to be distrusted or laughed at.

The July 2024 X Space Ruto walked into crystallised the shift. It was not a presidential address beamed in one direction. It felt closer to a live cross‑examination, a digital tribunal where callers interrupted him, demanded specific answers, read out bill clauses, and corrected numbers in real time while thousands of listeners layered jokes, memes and live commentary on top. It showed that he does not just face angry youth; he faces a generation that has grown up fact‑checking presidents while the president is still speaking.

Heading into 2027, he sits in a bind. He needs these platforms to reach voters who no longer treat TV news as their primary source, but his government’s own record of weaponising those same platforms has poisoned the well. In the logic of the feed, his image now carries a weight of accumulated stitches, duets and memes that present him as a symbol of betrayal around tax, debt and police violence, and algorithms are very slow to forget such consistent labelling.

TikTok as battleground, not billboard

Traditional campaign thinking treats TikTok like a new TV channel, somewhere you dump speeches, adverts and influencer endorsements, then hope something “goes viral.” In practice, TikTok behaves more like a crowded battlefield where attention is constantly fought over using in‑jokes, sounds and formats that do not respect political boundaries.

During the Finance Bill protests, politics travelled under the same trending audios as comedy and dance. A sound could carry a viral dance one moment and a clip of police shooting at protesters the next. Finance Bill explainers, skits about MPs and heartfelt testimonies from hospital beds all lived side by side, blending outrage and humour in ways that made it impossible to cordon off politics as a separate, easily monitored category.

This is what makes TikTok such a dangerous and powerful arena for 2027. Campaigns that speak the platform’s language, that accept jump cuts, story‑times, mistakes and self‑deprecating jokes, can humanise candidates and make policy surprisingly digestible in sixty seconds. The same dynamics can push fake clips, edited speeches and conspiracy theories about “deep state” plots into millions of feeds before any correction can catch up.

Consultants in Nairobi already tell parties to think like creators rather than billboard buyers. That means posting daily, reacting in real time, letting supporters remix content without panicking about message discipline, and treating mockery as part of the conversation rather than an attack to suppress. For a sitting president used to hierarchy and tight control, that is not a comfortable posture. It demands vulnerability in front of a generation that already sees him as the villain in their stitched timelines.

The quiet front: platforms, policy, and rule‑changes in the dark

While everyone watches the noisy content war on the surface, a more technical contest is unfolding backstage. Governments across the continent are exploring stricter rules for social media in the name of combating hate speech and extremism before elections. Platforms, stung by previous scandals, are quietly tweaking moderation systems and recommendation rules in “high‑risk” environments. Activists and civil society groups are lobbying both sides, trying to keep online civic spaces open without turning them into free‑for‑all zones for incitement.

In Kenya, you can already feel the tension in official statements that simultaneously warn youth against “misusing” social media and urge them to be “responsible” in shaping 2027. Church bodies and civic groups invite young people to flood digital spaces with messages of hope and accountability, while security agencies talk about clamping down on “toxic activism.” The same platforms that carried #RejectFinanceBill2024 could, under new policies, automatically down‑rank anything tagged as political or sensitive during the heat of the campaign.

This is where Ruto holds structural leverage that no influencer can match. As president, he sits in the rooms where governments and platforms discuss “election integrity” and “national stability.” His framing of what counts as harmful can subtly steer enforcement in ways that favour incumbency without ever issuing a public censorship order. Gen Z, by contrast, can dominate the visible feed yet have almost no say in how that feed is programmed in the first place.

The risk is simple and brutal. A stitched video calling out police killings or exposing broken promises can be flagged by an opaque system as dangerous disruption in the same category as explicit calls for violence. If platforms decide to reduce the reach of “political” content across the board, then the very energy that made Gen Z so effective in 2024 could be throttled in 2027 under the banner of neutrality.

From protest energy to electoral arithmetic

The final unknown is whether Gen Z can translate their mastery of attention into votes that actually move the electoral map. Their politics is horizontal, issue‑driven and deeply suspicious of parties. It is easier to unite them against a tax bill than behind a single candidate with a manifesto. Global studies of youth uprisings warn that such movements often succeed at blocking bad policies or shaking governments but fail to build structures that can govern afterwards.

Even so, your notes show early attempts to bridge the gap. Church networks and civic groups calling on youth to shape 2027 are pairing their speeches with concrete voter registration drives, online tools for checking registration status, and simple explainers on how to transfer polling stations. Some of the same coders who built protest bots are quietly testing “voter GPTs” and ward‑level dashboards that could track results as forms are photographed and uploaded on election night. Creators who made their names translating the Finance Bill into memes and Sheng threads are pivoting to series on debt, the budget process and devolution.

For Ruto, this emerging machinery cuts both ways. If he can find credible ways to plug into it, not just by hiring a few influencers but by giving young creators real agenda‑setting power, he might slowly rebuild trust where it has cratered. If he defaults to repression, astroturf campaigns and regulatory heavy‑handedness, he may win short bursts of quiet at the cost of teaching the algorithm, yet again, that he belongs on the wrong side of history.

Kenyan presidents used to win by owning buses, tents, loudspeakers and the loyalty of local brokers who could fill a field on command. In 2027, the crucial battle will unfold inside a more intimate, more unpredictable space, the few inches between a thumb and a glass screen. The generation that turned that space into a protest headquarters now intends to turn it into a polling station of the mind. The question for Ruto is not just whether he can reach them, but whether, when his face appears on their feeds, they still see a president or only a meme to scroll past.

-(3).jpg)

.jpg)

)